High Speed 2 should be rescoped to run from London Euston to Crewe, taking advantage of the lessons learned and supply chain foundations established during Phase 1, says Dyan Perry, Chair of the High Speed Rail Group.

s

High Speed 2 stands at a defining crossroads. Phase 1 from Old Oak Common to Birmingham has the green light, and under the new leadership of HS2 Ltd CEO Mark Wild the project is undergoing a positive and much needed ’reset’. With around 31 000 jobs currently supported, more than 75% of tunnelling completed and construction underway on two-thirds of HS2’s viaducts, momentum is building again.

This fresh injection of energy is welcome after years of shifting goalposts and cuts to the project’s scope. However, while Phase I pushes ahead, the handbrake has been pulled on the next critical phases of the project: the route from the West Midlands to Crewe and Old Oak Common to London Euston.

In the short term, this may appear fiscally sensible. However, as with all infrastructure investments, the project and potential returns must be viewed through a long-term lens. After all, a half-built railway moulded by short-term decision-making risks squandering investment to date and losing billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money.

Reflecting on this, the High Speed Rail Group’s spending review submission sets out six recommendations we believe the government must adopt to maximise HS2’s economic and capacity benefits going forward, while recognising current fiscal realities.

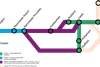

Our top ask is the re-scoping of HS2 to a ‘Euston to Crewe’ core. This vital part of the original planned route should be non-negotiable. It would act as a key driver of the government’s economic growth ambitions, going ‘faster and further’ to boost investment, generating jobs and boosting the UK’s supply chain. It would also provide additional and urgently needed national transport capacity between London, the West Midlands and the northwest.

Last year, following assessment from the Department for Transport, the National Audit Office reported that the West Coast Main Line will be at capacity by the mid-2030s. However, the WCML has arguably already hit its limits, due to its inability to accommodate growth now, not forgetting the government’s commitment to grow rail freight by at least 75% by 2050. Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham reiterates this concern, stating that not doing anything to address capacity on the WCML would be a ‘brake on growth’. HS2 was always intended to release this pressure and enable economic expansion. These are benefits that build over time, not overnight.

The encouraging news is that all the infrastructure required to deliver this core section has been granted parliamentary powers, and nearly all is funded, except for two crucial elements. Chief among them is the connection from the West Midlands to Crewe, which must be urgently greenlit before the powers to build it run out. Without it, HS2 cannot fulfil its purpose of alleviating pressure on the West Coast Main Line at its most constrained point. Additionally, this section can now be delivered far more cost-effectively than before, thanks to the lessons learned and supply chain foundations established during Phase 1.

Euston too is a critical piece of the puzzle. An initial six-platform design would be sufficient for day one operations and, as described by the rail minister, would futureproof the station for anticipated growth and potential expansion of the network. It does not need to be a gold-plated, high specification build; instead, a streamlined, cost-effective station design could yield a 35% cost saving, unlocking £3bn–£4bn.

However, justifying any extra spend is currently a big ask. That’s why finding a funding model that can provide the necessary financial firepower is essential. Having examined the figures, HSRG believes a concession let for a London to Birmingham and Crewe railway line, one that takes learning from the HS1 financing model, could generate between £7·5bn and £10bn in concession value, a significant return for taxpayers.

Significantly, there is precedent for this. When HS1 was under construction, it faced fierce opposition and serious cost pressures, but the decision to see it through paid off. In November 2010, a 30-year concession for its operation was sold for £2·1bn, recovering a third of the construction costs. But there is a catch for HS2. Without Euston station, and the connection from the West Midlands to Crewe, the value of a HS2 concession to HM Treasury would likely be at least halved. That’s billions of pounds in lost revenue, all because we didn’t complete the final miles.

Revisiting original ambitions often reveals new paths forward. HS2 was never just about speed, it was about releasing capacity, rebalancing our country, connecting rural communities, and supporting long-term national prosperity.

Under Mark Wild’s leadership, we have a real opportunity to realign with the project’s founding values, commit to a cohesive long-term plan, and deliver the railway Britain truly needs: one that is fit for the future. The time is now for government and industry to work together to get HS2 back on track and delivered.